“The Most Wonderful Time of the Year?” — When Christmas Is Hard on Mental Health

You know that moment — usually somewhere around the 47th playing of “Wonderful Christmastime” — when you catch yourself thinking: is it me, or is this all a bit much?

You’re standing in a supermarket that’s been decorated to within an inch of its life since late October. A man dressed as an elf is handing out samples of something called “Festive Brie.” Everyone around you appears to be executing Christmas with the calm efficiency of a military operation, while you’re still not entirely sure what day the bins go out.

And somewhere beneath the muzak and the panic-buying, a small voice whispers: I’m not sure I can do this.

If that voice sounds familiar, I’d like to suggest — gently, and with the authority of someone who has spent more than one Christmas hiding in a bathroom — that there’s nothing wrong with you. The problem isn’t your attitude. The problem is that Christmas, as currently configured, is absolutely bonkers.

But here’s the good news: once you understand why it’s hard, you can start making it easier. Not perfect. Not Instagram-worthy. Just… manageable. And sometimes manageable is exactly enough.

The Tyranny of Compulsory Joy

Here’s the thing about Christmas that nobody mentions in the adverts: it’s the only time of year when happiness becomes mandatory. A sort of emotional conscription. You will feel grateful. You will feel connected. You will wear the paper hat and laugh at the cracker joke, even though it’s the same joke from 1987 and it wasn’t funny then either.

But here’s what I’ve learned, sometimes the hard way: feelings are not obedient creatures. You can’t summon joy like a waiter. You can’t schedule peace and goodwill between the starter and the main course. Emotions arrive when they arrive, and they’re famously indifferent to the calendar.

The trouble is, when there’s a gulf between how we’re supposed to feel and how we actually feel, that gulf doesn’t stay empty for long. It fills up with shame. With the creeping suspicion that everyone else has figured out how to do this, and we’re the only ones faking it.

You know when you’re at a party and someone says “Isn’t this lovely?” and you have to arrange your face into something approximating agreement while internally you’re calculating exactly how soon you can leave without causing offence? Christmas can feel like that, but for an entire month. With relatives.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Christmas

I don’t wish to alarm anyone, but I’ve done some research — by which I mean I’ve watched television in December — and I can confirm that Christmas is exclusively celebrated by photogenic families in large houses with working fireplaces. Everyone has matching pyjamas. There’s always snow, but the cosy kind, not the “trains cancelled, pipes frozen” kind. A golden retriever is usually involved.

This is, of course, nonsense. Marketing fiction. The emotional equivalent of those food photographs where the “ice cream” is actually mashed potato because real ice cream would melt under the lights.

But nonsense, repeated often enough, starts to feel like a standard you’re failing to meet. If you’re alone at Christmas — whether by circumstance or choice — the world’s relentless insistence that this is a time for togetherness can make solitude feel less like a situation and more like a verdict.

The truth, which the advertisers would rather you didn’t dwell on, is that plenty of people spend Christmas alone. Or with people they don’t much like. Or with people they love but find exhausting. Family, after all, is just a group of people who happen to share some genes and, occasionally, some unresolved arguments from 1994.

The Ghosts of Christmas

Christmas, more than any other time, is haunted. Not by Dickensian spectres — though frankly, at this point, a visit from three ghosts might be a welcome distraction — but by absence. By the people who should be there and aren’t.

You know when you reach for the phone to call someone, and then remember? That small, daily collision with loss? Christmas concentrates those collisions. The empty chair at the table. The stocking you’ll never fill again. The traditions that belonged to someone who isn’t coming back.

Grief, it turns out, doesn’t much care for the festive schedule. If anything, the season’s insistence on nostalgia can bring loss into sharper focus.

And it’s not only people we grieve. For those in recovery, Christmas can stir a quieter kind of mourning: for the drink that used to take the edge off, the substance that made family gatherings survivable, the old familiar ways of coping that at least worked, even when they were killing us. Choosing sobriety during the season means sitting with discomfort that everyone around you is busily anaesthetising. It’s brave. It’s also bloody hard.

The Bit About Money and Noise

Let’s be honest: Christmas is expensive. Properly, alarmingly expensive. And for a lot of people, the financial pressure isn’t charming or manageable. It’s terrifying. It’s lying awake at 3am doing arithmetic.

Then there’s the sensory dimension. The crowds. The noise. The lights. The way every public space has been transformed into an aggressive tinsel assault course. For anyone living with anxiety, or depression, or a brain that processes stimulation differently, this isn’t festive. It’s overwhelming.

So Why Does Struggling Now Feel So Much Worse?

Here’s the particularly cruel part — and I promise I’m building to something genuinely useful, so do stay with me.

Struggling at Christmas feels more shameful than struggling at any other time. Because if you can’t manage to be happy now — when the entire apparatus of Western civilisation has been arranged specifically for celebration — then surely something must be fundamentally wrong with you?

This is, to use the technical term, complete rubbish.

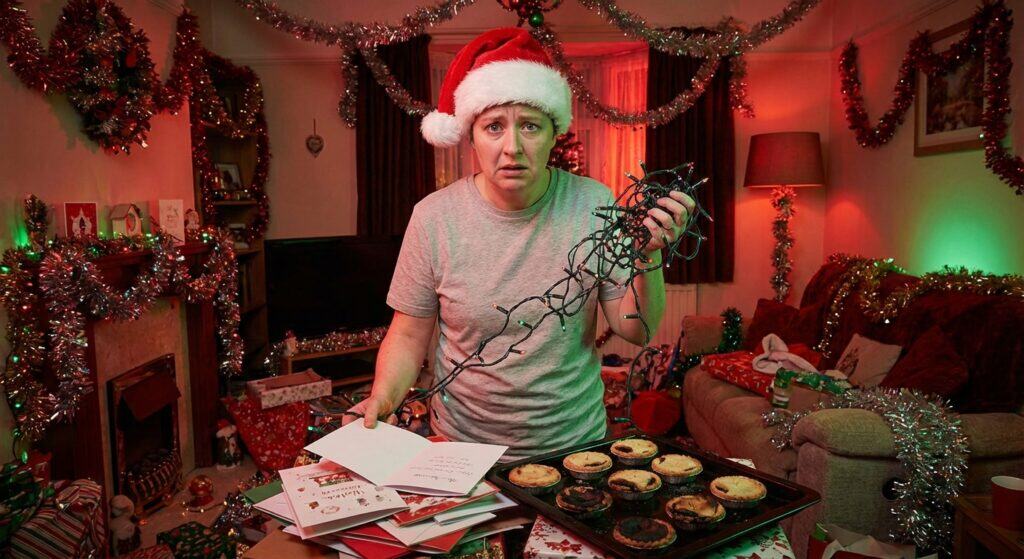

Think about what Christmas actually asks of you. Maintain complex family relationships across multiple generations. Spend money you may not have. Abandon your normal routines. Navigate social situations while running on mince pies and inadequate sleep. Process grief, loneliness, and financial stress while everyone around you insists on having a lovely time.

That’s not a holiday. That’s an endurance event with crackers.

Your struggle isn’t a sign that you’re doing Christmas wrong. It’s a completely reasonable response to an unreasonable situation.

Which brings us to the actually useful part.

What Might Actually Help

I’m not going to tell you to “practise gratitude” or “focus on what really matters.” You’ve heard all that. It’s not wrong, exactly, but it’s a bit like telling someone who’s drowning to “think about how nice the water is.” Technically possible. Not immediately helpful.

Instead, here are some things that might actually make a difference:

Lower the bar. Then lower it again.

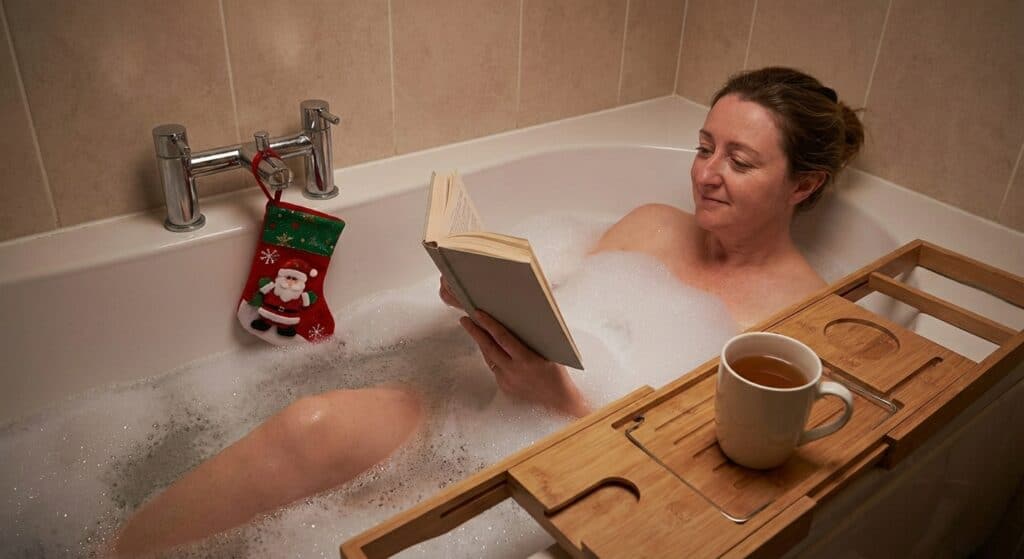

You know when you’re ill and you abandon all ambition beyond “exist horizontally and drink tea”? That’s not giving up. That’s wisdom. You’re matching your expectations to your actual capacity.

Christmas can work the same way. What if “good enough” was the goal? What if the house didn’t have to be spotless, the gifts didn’t have to be perfect, and you didn’t have to say yes to every invitation? What if you decided, in advance, that some things simply weren’t going to happen this year — and that was fine?

The freedom of lowered expectations is vastly underrated.

Plan your exits.

This one’s practical. If you know certain situations are going to be difficult — the family lunch, the work party, the afternoon when everyone’s had too much to drink — plan how you’re going to leave. Drive yourself if you can. Have a ready-made excuse that doesn’t require elaboration. “I’ve got an early start” is a complete sentence.

You know when you’re on a plane and they show you where the exits are, and you feel slightly calmer even though you’re not planning to use them? Same principle. Knowing you can leave makes staying bearable.

Give yourself permission — in advance.

Here’s a useful exercise: before Christmas properly starts, write yourself a permission slip. Not metaphorically. Actually write it down.

I give myself permission to leave the party early. I give myself permission to not drink. I give myself permission to skip the Boxing Day gathering. I give myself permission to feel sad, or tired, or overwhelmed, without apologising for it.

It sounds silly. It works anyway. There’s something about making the decision in advance, when you’re calm, that makes it easier to honour when you’re not.

Know the difference between coping and avoiding.

This is where I have to be a bit more serious for a moment.

There’s a difference between protecting your energy and hiding from your life. Between saying “I need a quiet evening” and never leaving your room. Between not having a drink and having no way to cope without one.

If you notice that your strategies for “getting through” Christmas are starting to look a lot like the things that got you into trouble before — isolation, numbing, pretending everything’s fine when it isn’t — that’s worth paying attention to. Not with judgement. Just with honesty.

Reach out before you’re drowning.

You know when your phone battery gets to 5% and you think “I should probably charge that” and then you don’t, and then it dies at the worst possible moment? Mental health works similarly.

The time to reach out isn’t when you’re in crisis. It’s before. When you notice the warning signs. When you’re at 20% and can still have a conversation about it.

This might mean telling someone you trust that Christmas is hard for you. It might mean calling a helpline not because you’re desperate, but because you want to talk before you get there. It might mean booking an appointment with a therapist in January, so you have something to look forward to on the other side.

Asking for help when you’re struggling isn’t weakness. It’s the same as going to the doctor when you’re ill. It’s just… sensible.

A Different Kind of Christmas

Here’s what I’ve come to believe, after enough Christmases to spot the pattern:

The version of Christmas we’re sold — the perfect, joyful, connected celebration — isn’t real. It’s a collective hallucination, maintained by advertising budgets and social pressure and the fact that nobody wants to be the first to admit they’re finding it hard.

But there’s another version available. A smaller, quieter, more honest Christmas. One where you do what you can, feel what you feel, and let the rest go. Where “getting through” counts as success. Where asking for help is a sign of strength, not failure.

This Christmas might not be wonderful. It might just be okay. And okay, when you’re carrying a lot, is actually quite an achievement.

Be gentle with yourself. You’re doing better than you think.

If Christmas feels like too much this year, you don’t have to manage it alone. Whether you need someone to talk to, support for your mental health, or help with recovery, reaching out is always the right choice.Visit our mental health services pagehttps://promis.co.uk/treatment/mental-health to learn more about treatment options, or contact the Samaritans helpline for immediate support.